Tommy Lee Jones is stranded far away from Texas in this HBO films TV-adaptation (2011) of Cormac McCarthy’s play. The reclusive author’s signature dance at the edge of nihilism and profundity is a perfect fit for Jones the director and actor, resulting in a work of rich dark tones.

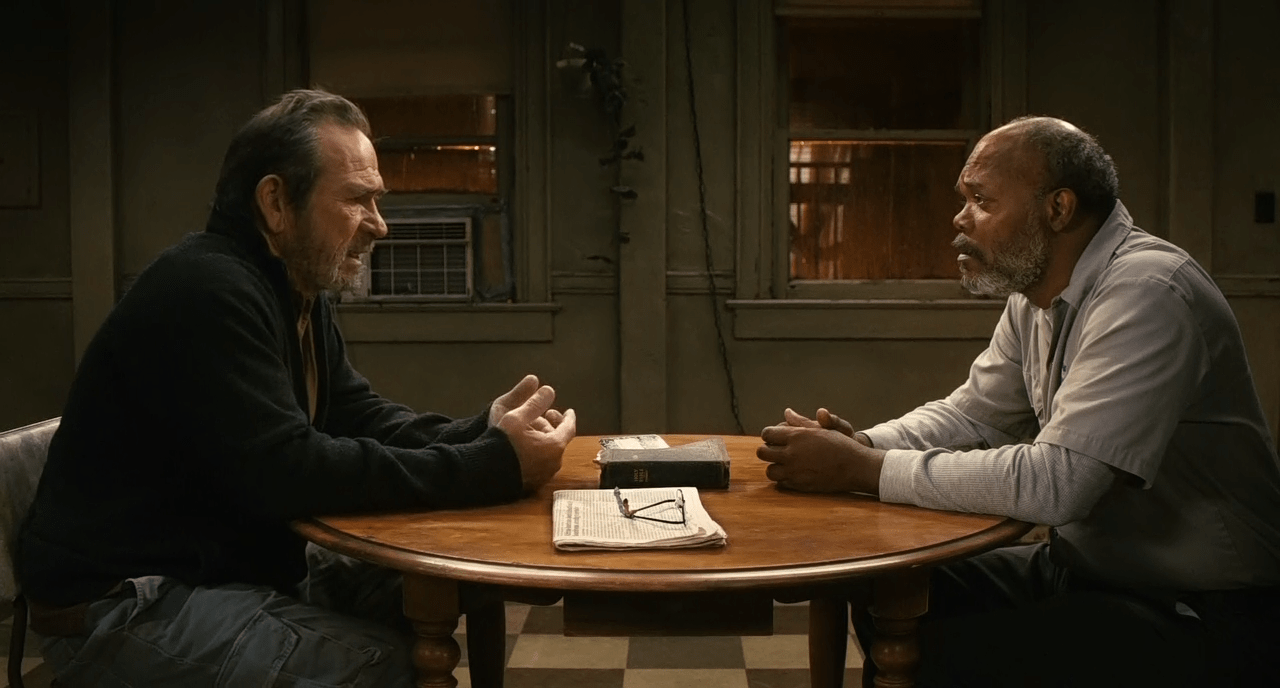

Two men, a black (Samuel L. Jackson) and a white one (Tommy Lee Jones) are sitting in a small and downbeat New York apartment. As we find out, the white man, an atheist university professor, tried to kill himself by jumping in front of the Sunset Limited train, but this black Christian ex-convict saved him, took him to his apartment and now he is trying to talk him out of suicide.

The uneducated Louisiana ex-convict with a violent past who turned to religion from his destructive ways and has been saved and the middle class New York intellectual lamenting the end of culture and its devaluation could easily become stereotypes, but they never do.

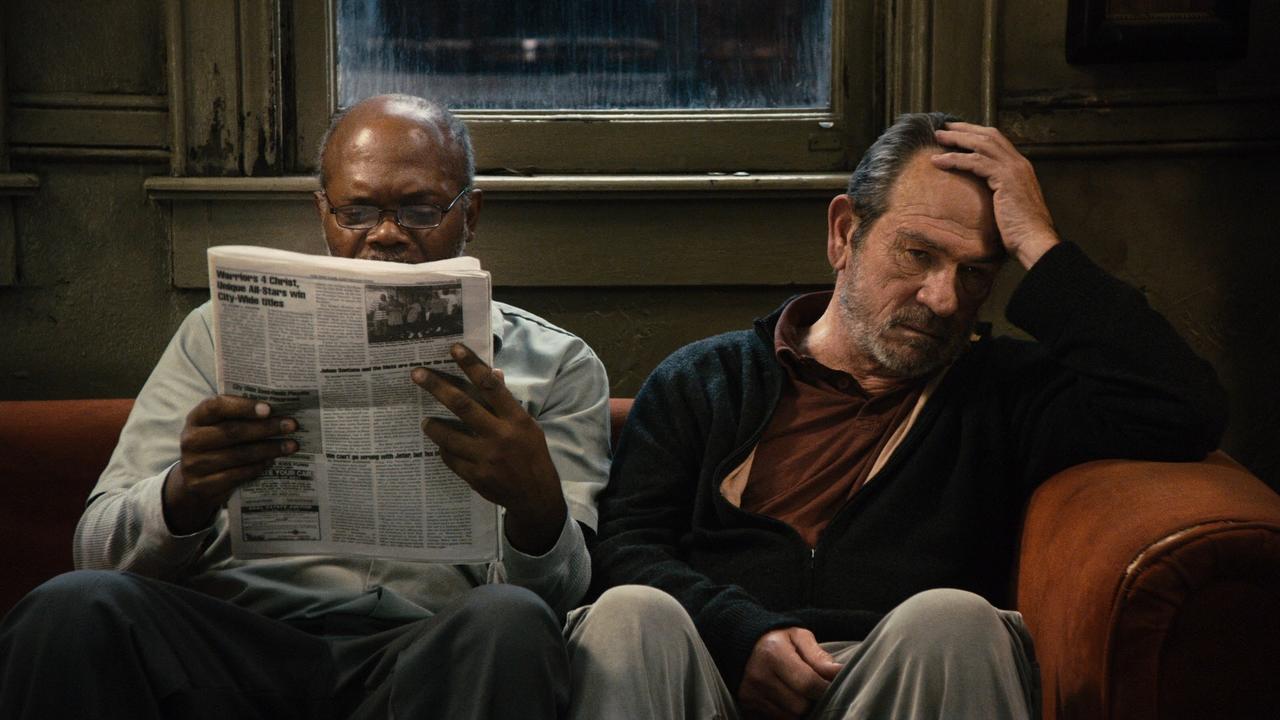

The two leads are both excellent and make the most of their on-screen dynamic. Jackson gets a chance to bite into monologues with his well-known zeal in a role that plays to his strengths but also shows a combination of gifts we haven’t quite seen from him yet. There is a mellowness, a wiseness, a natural inquisitiveness and a great sense of humour formed out of a hardened life. Jones who often plays roles with sparse dialogue, skilfully carries off tirades of an existential abyss, his natural dialect toned down, wearing a cardigan and a light beard, he immediately and unnoticeably passes for a university professor.

McCarthy and the filmmakers bravely refuse to concede to typical notions of what a two person play/film is supposed to be. There is an “exit”, and although in one of White’s monologues we get something akin to “hell is other people”, it is truly special how much respect and congeniality breathes in this one room, despite having two characters who are in conflict with one another. There is barely a moment where you know where this story is going.

This is not a play about two people in a confined space resorting to barbarism and trying to outwit and defeat one another. Although the threat of violence is sometimes distantly in the air, the tension comes from opposing worldviews and my long term attention was firmly held by the intellectual and emotional stimulation that these arguments provided. I was riveted by the possibilities of who these two people are and what they could mean to each other. It was like getting to know someone who proves to be endlessly interesting. “Tell me more about that!” – I talked at the screen.

Chekhovian guns of personal information remain daringly unspoken, un-utilized and unexplored. McCarthy is so confident in the power of his words and the lack of them, that he never once falls into the trap of treating his scenario as one of limitations. He does not try to milk every single notable element for maximum tension or dramatic potency. He has all his ingredients and he lets them speak for themselves with the endless promise that any living being or inanimate object can express. Jones admirably follows suit and does not try to make the play action-packed or something that it’s not. The opening shots of the uninhabited space of a New York subway station, the arriving Sunset Limited, then followed by walls and different objects, e.g. chairs in Black’s apartment make the small aspects of everyday life monolithic and brimming with possible meaning. Is Jesus, or anything you might want to call it, but something absolute truly present in all things? If you can’t see it or feel that it is present, can you choose to or wish to feel it? In The Sunset Limited, Jones and McCarthy are in deeply metaphysical territory.

The constant challenge with adaptations of plays is how to make them cinematic. Jones seems to almost sidestep, or rather invert this question entirely. There are no flashy camera moves or jump cuts, yet it all comes alive by the skilful use of off-screen sound that subtly breaks the silence of the decrepit apartment. The film seems to be about what we can’t see just as much as what we can. The barely caught arguments of junkie neighbours, the blasting hip hop music, and the obscure street noises all speak of a world beyond what we can see, yet the seemingly limited space gains notable magnitude. There is a whole world inside each of these two men that have unlimited depths but might disappear just as easily into obscurity or nothingness.

Jones’ frequent collaborator Marco Beltrami’s experimental and minimalist score forcefully suggest such ambivalent meanings and ambiances, and beautifully assists Jones in one of the film’s darkest scenes where White finally shares the true depths of his despair.

Who knows what will happen to these people? For a short time, there is a kinship and a recognition of each other’s humanity. Maybe that’s all that matters.

Rating: 82%