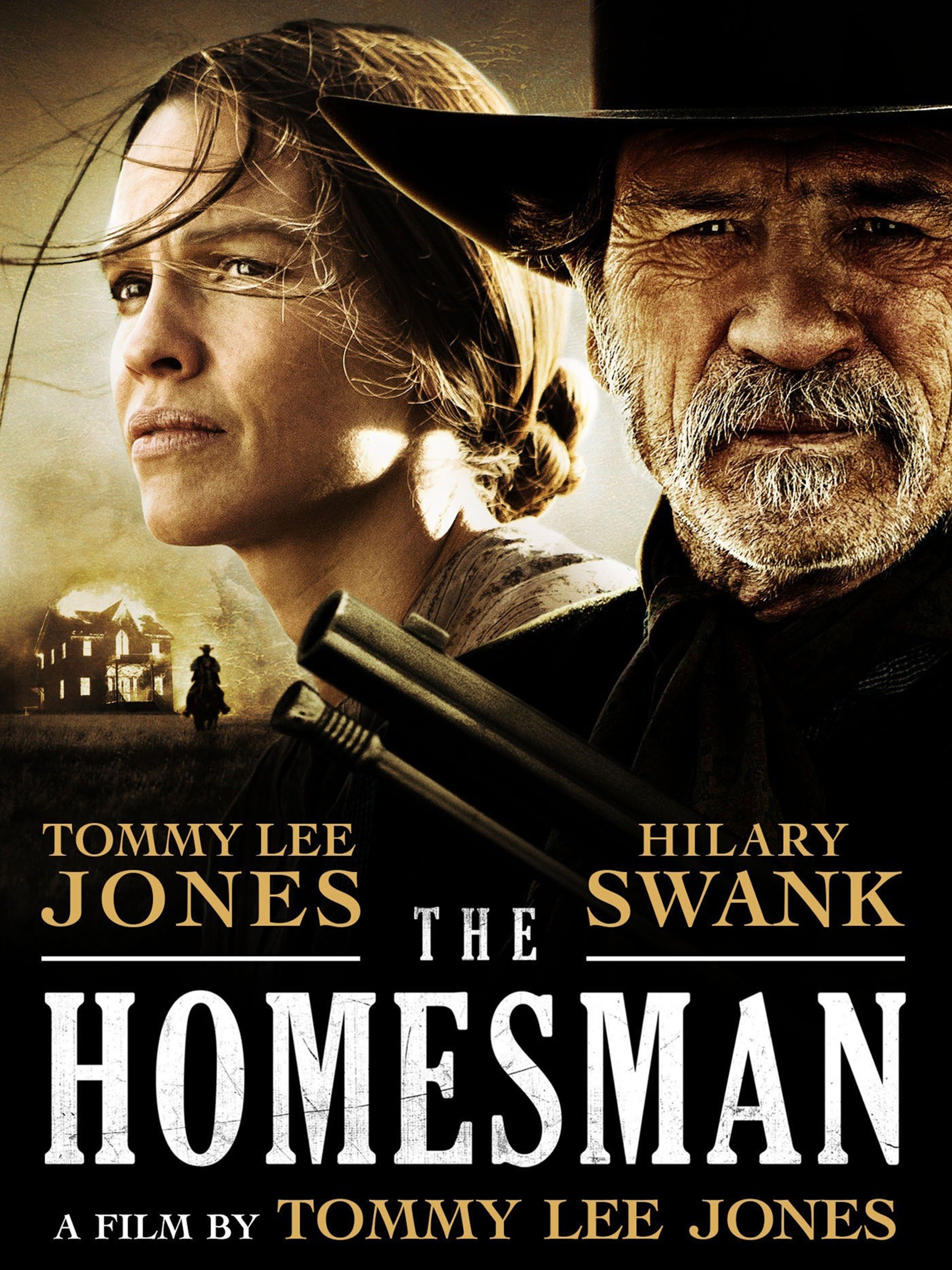

You can read the map of Texas into the face of Tommy Lee Jones. The prolific actor’s fourth effort (2014) as a writer-director-producer is a deconstructionist western that scars and enlightens in equal measure.

Lately I have been on a binge of the Texan’s movies. As his screen presence is having a lasting impression on me I have no choice but to scavenge for some kind of answer, even if there isn’t one. Part of his appeal stems from his ability to suggest multiple meanings both as an actor and director, despite appearing forthright, even simple on the surface.

This ambivalence is powerfully present in The Homesman. A film many touted as a feminist western, it tells us a tale of uneasy partnership between a woman and a man as they escort three women who lost their minds under the harshness of pioneer-life, across the river back to Iowa. There are beautiful, sunlit vistas of the plains that no director could resist that help pull us in, only to be gobsmacked by the frankness of what follows.

This is a story of female bodies, broken down, used, with no regard for the soul inside. Flashbacks tell interlaid tales of a terrible winter and slowly encroaching madness, with Marco Beltrami’s versatile score unleashing existential despair worthy of horror. This might be the first film of its kind that unapologetically and thoughtfully shows what it must have been like to be a woman in the Wild West.

In the role of the religious, self-reliant and deeply compassionate Mary Bee Cuddy, Hilary Swank does some of her best and most subtle work as an actor. Her commanding presence and androgynous visage is of a woman who has plenty of bottled-up sadness. It appears she was born into the wrong century where her natural capabilities make her unfit for marriage in the eyes of many, while the social expectation is clearly there. Her loneliness is etched into her eyes as she looks at you. ‘So why not marry?’ The way she gets rejected more than once as she practically begs for love and acceptance is heart-breaking to watch. It is a performance of true thespian bravery without any moments of showiness.

Jones, in the role of George Briggs also has remarkable colours as he subverts his own image to an effect akin to the clumsiness of Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven, where a retired killer turned hog-farmer fell left and right into the mud and off a horse, with pitiable gracelessness. This seasoned gunfighter doesn’t return to being an unstoppable killing machine, if he ever was. He is an unholy scavenger of sorts whose being is about taking and taking for survival without giving anything of himself. Even his name appears to not be his own, but one that became available. Jones alternates between the more well-known gruff stoicism of his most famous characters and his public persona, a surprisingly agile merriness, a slimy rascality and cowardliness. A scene where he begs Mary Bee to save his life is the most vulnerable and weak we have seen him in recent memory. Briggs is a far cry from the uprightness of Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (No country for old men) or the might of US Marshall Samuel Gerard (The fugitive). What is most fascinating and moving to watch is how he may or may not be growing a spine before our eyes.

The screenplay’s (adapted from Glendon Swarthout’s novel by Jones, Kieran Fitzgerald and Wesley A. Oliver) well developed characters and the actors inhabiting them allow us to see people who are many things. As the inklings of their own identity clash against the gendered expectations of the times, their interactions create unexpected moments and unconventional meanings within the frame of the genre. Cuddy’s and Briggs’ pious versus godless temperaments even serve as a source of humour. We are in a territory of such existential bleakness that to laugh is the only way to make sense of it all.

Can the Homesman find redemption, and earn a second chance? Jones the director seems deeply appreciative and grateful to women, to womanhood, and the life they give, in all its forms. At risk of sounding presumptuous, the film sings like a love letter and a late-in-life mea culpa for wrongs and ‘taken for granteds’ committed in one’s younger years. With his assured handling of disparate tones, plot-driven scenes, and seemingly trivial moments, that somehow makes it all congruent parts of a whole, Jones stages a pyre where sins are burnt in the hope that it is not too late. There are no easy answers, only questions dancing inside a mind, fading and remorseful. Without women, without creation and nurture, what else is there?

Rating: 86%