Ad Astra is one of the most immersive experiences I have ever had at the movies. A powerful character study and dissection of masculinity and parent-child relations, dressed up as a sci-fi adventure. If you are patient, it will leave a mark on you.

Roy McBride (Brad Pitt) is an astronaut who is much more capable in life-threatening situations than in personal relationships. As his wife Eve (Liv Tyler) leaves him due to his emotional unavailability, he is tasked with a high-stakes mission to save mankind from cosmic ray surges coming from the direction of Neptune. What further complicates matters is that Roy’s legendary father Dr Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones) is most likely responsible after disappearing on a mission 16 years prior. On his voyage towards the other end of the solar system, what will he find? If you avoid life itself, you might as well be dead.

Writer-director James Gray uses the genre elements of sci-fi to strengthen a character study, with space serving as a metaphor for Roy’s loneliness. He both deconstructs and cannibalizes the sci-fi genre, just as in one scene a lab primate on a mayday ship tries to devour a space captain in one of the film’s tensest scenes; it is effectively devouring its own image. Gray shows this conflict to reflect on the primal destructiveness of the human race, and of the masculine. Rage is a mask we wear when we are afraid.

This vision of space moves away from the transcendental, with the endless emptiness providing both awe and horror. The search for intelligent life becomes an excuse for the mental journey of the father and the son, as their self-absorbed search leads them towards complete solitude and alienation.

Some of these emotional beats are slightly overstated by the voiceover (sensitively rendered by Pitt), but without it we would hardly have any insight into who Roy really is. This closeness to the character and the limitations of his point of view makes Ad Astra the epitome of the naval-gazing film, however this shouldn’t trouble viewers readied bySolaris(1st and 2nd adaptations) or 2001: A Space Odyssey. While the comparisons are easy to make, this slow-fi has a different approach.

The future is high-tech as usual, commercialized and amenitized, desolate and lifeless in its perfection, but the point of view is more intimate and psychological, with emotion being a mistake to be avoided. The art direction has a minimalism, with visual projections being prioritized. Most of what we see on screen is a representation of the lead character’s psyche. Gray’s direction beautifully uses birth metaphors, an underground lake, feeding tubes standing in for breastfeeding, and most emblematically, a space cabin that is both a womb and a coffin, life and death.

Brad Pitt gives one of his strongest performances to date as Roy. He is front and centre, the canvas for it all. Gray uses his image of iconic masculinity to dissect male myths of power and control. As he holds back on emotions and subdues his live-wire energy often displayed in other films, his presence grows larger and all the more magnetic. As the character’s façade of emotional suppression and monolithic manliness starts to crack, Pitt shows us a side so naked and vulnerable that it feels like an invitation into his soul. Roy, despite his exceptional abilities and promise, is a lost little boy, copying his father. He gives up on human contact for the gratification of staying in control, however with a deep sense of guilt and the flickering hope of learning how to feel. The parental tentacles are reaching across space. What is the price of freedom?

Jones is appropriately Kurtzian and mercurial as Clifford. A megalomaniacal, paranoid and unemotional zombie of cold egotism, he is running away from real life and humanity.

While one could credibly accuse the filmmakers of wasting the talents of Liv Tyler, her character/performance works very well as a walking symbol of all the good that Roy leaves behind and will hopefully return to. “I have my own life. I am my own person.” – She says. Her fragmented depiction suggests that Roy never really knew her or was able to care enough to truly notice who she is.

Although this is a male-oriented film, somewhat balancing the scale is Ruth Negga as facility director of Mars, Helen Lantos who also has a personal connection to the mission. She suggests the depth of her character’s history and inner life with limited background information and just a few glances.

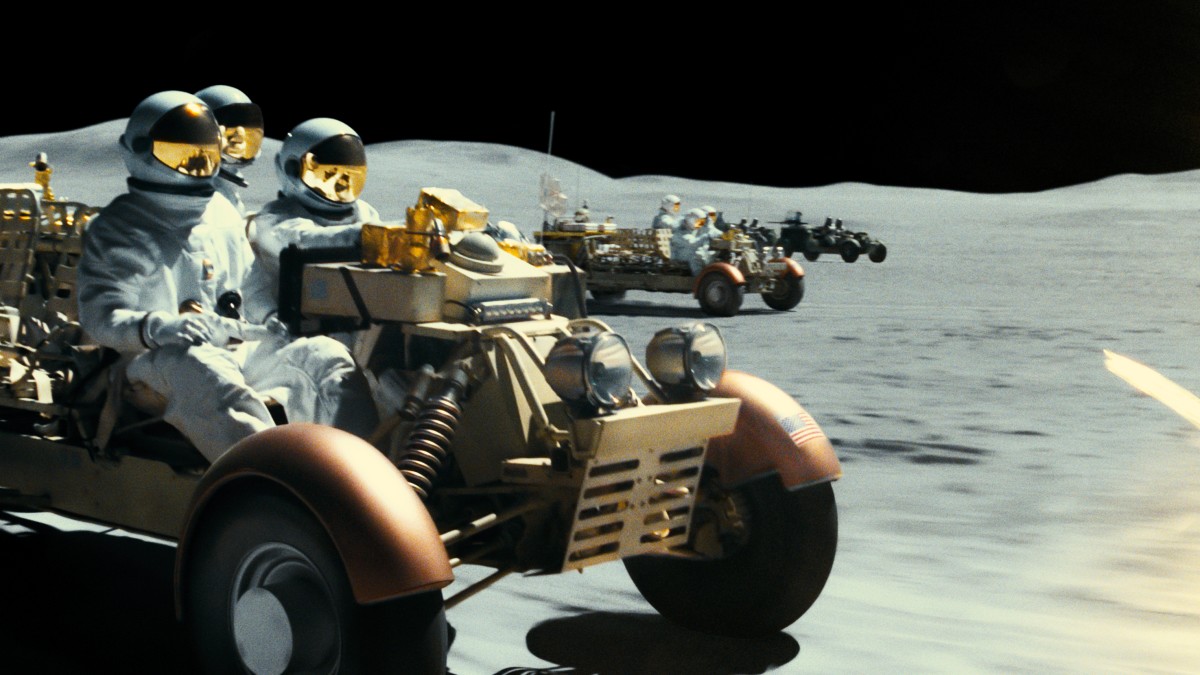

The most remarkable aspect of Ad Astra, is how far it carries the syntax and depth of an art film, while still giving us some exhilarating scenes of space adventure, with Gray holding them off for such a long period that when they arrive, they hit with full dynamism. The special effects are excellent, but it is the direction that makes it feel seamless and real. Gray is wonderfully assisted by Hoyte van Hoytema’s cinematography that is minimalist yet rich in texture within its decidedly limited colour palette. Max Richter’s score is deeply evocative with just a few basic themes. It is alternately mysterious, brooding, horrifying and has a profundity that is fully earned. I could feel the immense power of what being in space might be like.

When Ad Astra came out in September 2019, it was a critical success but a commercial flop. The studio made the mistake of advertising the film as an action-packed genre piece rather than the meditative art film it really is. The big budget and star power behind it could also have been misleading. For me personally, it is my favourite film of 2019.

This is a story of fathers and sons, of man’s path to find his place, not in destruction, but in harmony. There is no other life in the universe, but only on Earth. The lone wanderer is finally ready to step out into the real world, and be somebody.

Rating: 91%